“I cross out words so you will see them more....”

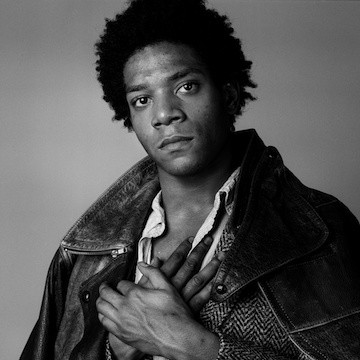

Jean-Michel Basquiat

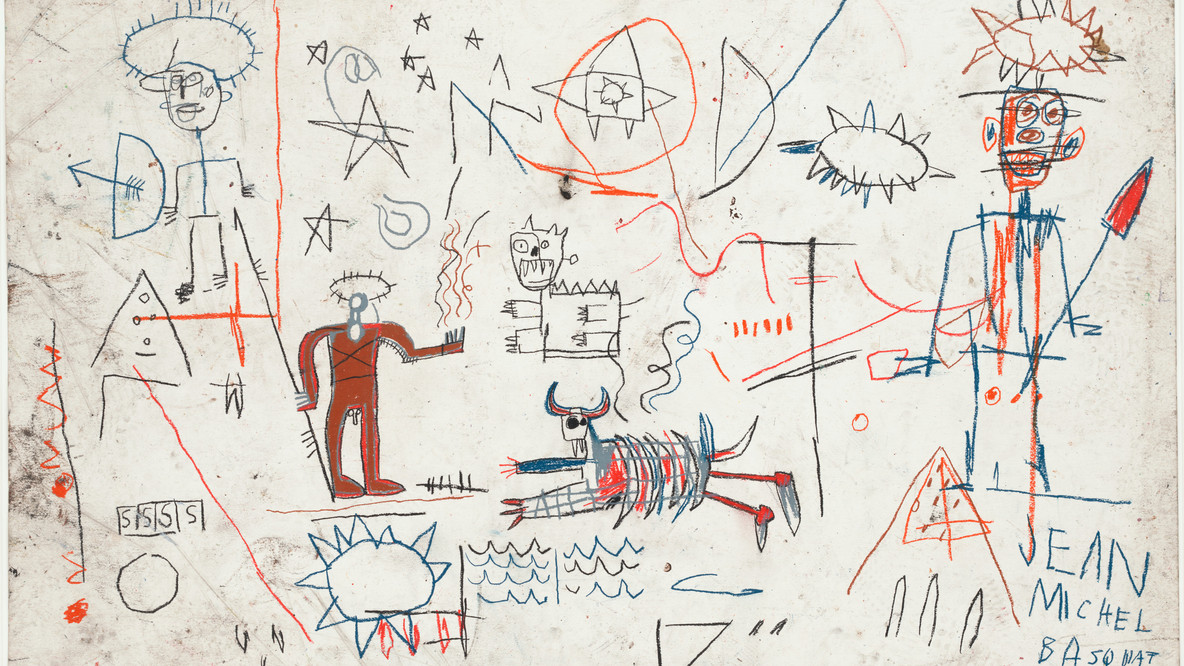

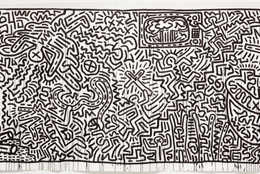

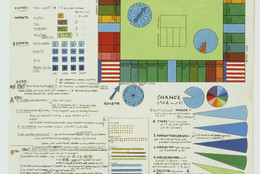

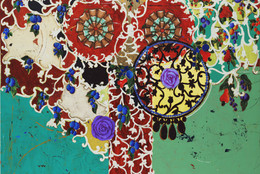

When asked to describe his art, Jean-Michel Basquiat responded with customary aplomb: “royalty, heroism, and the streets.” A high school dropout, Basquiat found his true calling hanging out in the streets and inserting himself in the bustling urban milieu, ultimately becoming an influential figure in New York City’s Downtown, especially the East Village club scene. He was a regular among a group of filmmakers, artists, and musicians who made the Mudd Club, Club 57, and CBGB their stomping ground. Basquiat achieved his breakthrough in the early 1980s, developing a unique vocabulary characterized by repetitive images, human heads with open mouths as if in speech, a variety of marks, and xeroxed collage. In his paintings, the patches of intense color, created with acrylic, oil stick, and graphite, keyed into the excitement of New York’s subculture.

Words mattered to Basquiat. He used them in a range of ways, either for their implicit meaning or to scar the surfaces of canvas or paper. Graffiti marks appear throughout his compositions as invocations or unfathomable musical notes. Cultural references such as “same old, same old” or “same old shit” are compressed into a convenient one-liner, “SAMO,” which was Basquiat’s moniker when he was a graffiti artist in the late 1970s, and later became his signature. Sunken, skull-like human faces with bulbous eyes, silted noses, and visible teeth—as well as anatomical sketches, diagrams, and medical terminology—recurred prominently in his work. They recall the months the artist spent convalescing in the hospital after he was struck by a car when he was eight years old, in May 1968. The accident cost him his spleen. To keep his mind off his injury during his time in the hospital, his mother bought him a copy of the British surgeon Henry Gray’s Gray’s Anatomy, a book that would later have a profound influence on his art.

The names of famous Black male cultural figures—music and sports stars including Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, Floyd Patterson, and Cassius Clay (Mohammad Ali)—are etched on his canvases as affirming cultural signifiers for Basquiat’s art on his way to stardom. He had a predilection for crossing out words or phrases in order to activate rather than obscure them. As he once explained to a friend, “I cross out words so you will see them more: the fact that they are obscured makes you want to read them.”

The years 1981 to 1986 was a rollercoaster period of creativity for Basquiat, who became a bona fide art-world star. His large canvases, vibrating with color, marks, form, and text, more than made up for his noticeable reticence and awkwardness in the limelight. His animating art, charismatic personality, and premature death from a heroin overdose at 27 years, in 1988, inscribed his enduring celebrity.

Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi, Steven and Lisa Tananbaum Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture, 2021